Who's at the Table?

Investigating America's Developing Composite Nationality During Reconstruction.

INTRODUCTION TO OUR PROJECT

Welcome! As a project for the New-York Historical Society's Student Historian Internship, we've combined our separate blog post projects on "Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner" and The Obadiah Letters to create this StoryMap. Our StoryMap highlights one perspective of our program's greater theme: "Our Composite Nation." A sometimes overlooked part of the Reconstruction era is how it was a time of growing diversity and composite nationality in the United States. Using Thomas Nast's famous illustration, "Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner," we will highlight what citizenship, freedom, and equal rights meant for all Americans during the Reconstruction era, with a special emphasis on indigenous peoples. Enjoy!

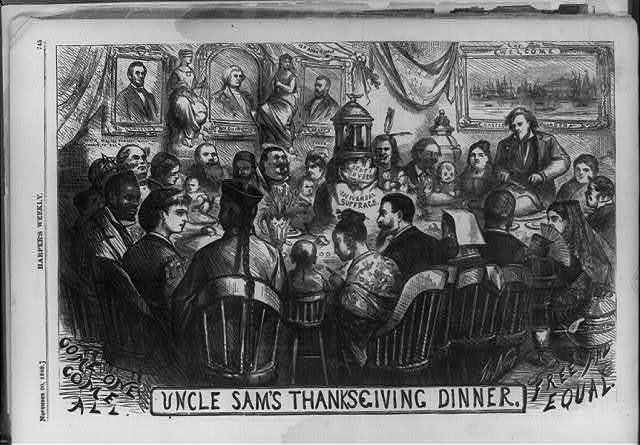

Thomas Nast, a prominent political cartoonist in the 1860s, published "Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner" in an 1869 issue of the Harper's Weekly magazine. The cartoon depicts a Thanksgiving dinner shared amongst Americans of different historically marginalized communities, including Irish, Chinese, Black, women, indigenous, and more. While Nast's cartoon displays a positive message, it must be recognized that he uses stereotypical imagery that today's standard would not accept. For instance, he portrays the Native Americans with feathers. In the lower corners of the illustration, the words "Come One Come All," and "Free and Equal" display an inclusive message. All around one table with Uncle Sam at the head, the diversity of American society is symbolized. Nast's theme is one of acceptance and unity, as all the immigrants are welcomed to the table by Uncle Sam. The many cultures that comprise the United States are represented in Nast's work, giving each viewer a metaphorical place at the table and in our nation.

Thomas Nast, "Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner," Harper's Weekly, 1869. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society.

THE ORIGINS OF THANKSGIVING DINNER

As the story of Thanksgiving is told nowadays, the Wampanoag people taught the struggling colonists how to survive in the New World, and had a feast to celebrate the first successful harvest. While literature and television have depicted this image of the Pilgrims and the First Thanksgiving countless times in our contemporary era, historians have long since debunked this mythologized origin story.

By the early nineteenth century, Thanksgiving was far from a national holiday. It was an optional local festival. Occasionally, presidents declared national days of Thanksgiving. A woman named Sarah Josepha Hale propelled Thanksgiving into a national holiday. In 1827, she published a two-volume novel titled Northwood; in 3 supreme court nomination hearings or a Tale of New England, which compared life in the North to the South. She included an entire chapter on Thanksgiving dinner, and commenced a campaign to make it a national holiday in 1846. Hale believed that Thanksgiving would reunite the nation at a time when sectionalism, economic self-interest, and slavery tore the country apart. During the Civil War, when campaigning was difficult, she wrote to the Secretary of State, Willaim Seward. She requested that he negotiate with President Lincoln about making Thanksgiving a national holiday. In 1863, President Lincoln declared the fourth Thursday of every November Thanksgiving and created a new national holiday. The late 1880s gave rise to the Thanksgiving story as we know it, with Pilgrims and indigenous people sitting at long tables eating clam chowder.

While based on a tale, Thanksgiving served to unite the United States at a time of division. It has become a building block of our national identity as we reconstruct the nation and become more diverse. Nast is signifying that this newfound unity is not just between White men, but everyone in our growing country. Thomas Nast uses the sense of unity that runs through the Thanksgiving holiday to further symbolize his cartoon's message. The illustration exemplifies Nast's ideas of embracing this diversity and composite nationality.

It's important to note that Thomas Nast was a white man, and this cartoon's story of Thanksgiving lacks an indigenous perspective. Indigenous people throughout the United States today have varying views on the Thanksgiving holiday. For many indigenous communities, Thanksgiving is considered a day of mourning to commemorate the genocide of millions of people after the arrival of the Europeans. Native Hope is a non-profit organization whose mission is "to dismantle barriers and inspire hope for Native voices unheard." To read a blog about Native perspectives on Thanksgiving, click here !

NAST CARTOON ANALYSIS

Black Americans

One of the groups represented in the cartoon is a Black American man and woman across from Uncle Sam. Black activism grew as people resisted the unequal laws that remained even after the Civil War. Black people organized Equal Rights Leagues and held conventions to protest against discrimination and for suffrage and equality before the law. A convention of Freedmen met in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1865 to demand new rights for Black Americans, specifically education for children. They formed a new resolution that recognized "knowledge is power." Since educated people cannot be reduced to slavery, good schools must be accessible to children in every neighborhood throughout the state.

Other notable figures supported education for Black Americans, including Frederick Douglass. He was a prominent abolitionist and fought for government action to secure land, voting rights, and equality for Black Americans during Reconstruction. In his speech "What the Black Man Wants" to the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society in 1865, Douglass explains that Black people want the right to vote because it is not only their human right but a means for education. Without suffrage, the freedmen are labeled as unfit to make an intelligent decision about public measures. Douglass believed that if given the opportunity and space, Black people would seamlessly harmonize into American society. During Reconstruction, Black Americans joined politics for the first time, with over 600 African Americans serving in state legislatures and 16 even serving in Congress. Just as Nast portrayed in his cartoon, Black people fought for and gained a voice as American citizens during Reconstruction.

Chinese-American

Chinese-Americans were another group of people whose struggles were also apparent during Reconstruction. Alongside the California Gold Rush came the perception that Chinese immigrants aimed to take jobs and profits away from American citizens, an anti-Asian sentiment common among White Americans at the time.

This increased immigration and growing Anti-Chinese sentiment led to the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. This law prohibited Chinese immigrants from entering the country and made it nearly impossible for those already living in the US to become citizens.

These circumstances, however, are what led activists like Wong Chin Foo to proclaim a new identity for Chinese immigrants by coining the term "Chinese-American'' which blurred that line of separation between being an outsider and being an American citizen. Sentiments like this united the community and incited them to fight for their rightful status as American citizens. Ng Poon Chew was another prominent Chinese American labor leader and community organizer who worked tirelessly to advocate against the Chinese Exclusion Act. He played a significant role in organizing and mobilizing the Chinese American community to fight against the Act and promote the rights of Chinese immigrants in the United States. Chew was a key figure in founding the Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance, which became one of the country's most powerful labor unions. He also founded the Chinese American Voters League, which worked to promote political representation for Chinese Americans.

Women

Perhaps most surprising about Reconstruction is its failure to meaningfully address the issues American women faced at the time. Despite not being granted equal rights to men, women were highlighted in Nast's cartoon alongside other oppressed groups. Nast displays the slogan "Universal Suffrage" at the center of his work in an effort to simultaneously promote voting rights for Black Americans and women.

During Reconstruction, abolitionists and feminists often had similar aims, and thus they shared resources and platforms to further their overlapping causes. In fact, Frederick Douglass believed that voting rights should extend beyond the confines of gender. Douglass frequently promoted the notion that abolitionists should work alongside feminists, advocating for the pooling of resources between the two groups. Elizabeth Cady Stanton was one of many prominent figures in the fight for women's rights during the Reconstruction era. As a key force in hosting the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, she helped make history in shifting the focus of civil rights advocates to the feminist cause. Stanton also worked to abolish slavery and promote civil rights for African Americans. Her advocacy for women's rights and abolition intersected with that of Frederick Douglass. Stanton collaborated with Douglass to found the American Equal Rights Convention in 1866. During that time, they both spoke out in favor of universal suffrage for all citizens, regardless of race or gender. However, when the passage of the 15th amendment granted voting rights to Black men, Stanton resorted to racist and nativist language, arguing that white women should have received the ballot first. The American Equal Rights Association disbanded. Douglass did not agree with Stanton's language or prioritization of the feminist cause over always promoting both Black and women's suffrage equally.

Indigenous People

Nast's cartoon has a Native American man seated just right of the universal suffrage centerpiece, with a red feather atop his head. This stereotypical caricature does not point to a specific Native American tribe but lumps all indigenous cultures together, which was wrong, yet common during Reconstruction and even nowadays. The Indigenous American experience during Reconstruction varied widely based on geographical location and tribal group. However, a series of letters from the New-York Historical Society collection gives insight into the experience of a sect of the Eastern Cherokee Nation. The Obadiah Letters are a series of letters initiated by a Cherokee man named James Obadiah. He sent letters to multiple people to receive the compensation that the government promised Cherokees for moving to a reservation, which was yet to be paid. Obadiah only had loose connections to those who could provide this help, yet he continuously advocated for his group, their government-promised rights, and compensation through these letters.

After the Indian Removal Act in 1830, the Cherokees were forced to leave their homeland in North Carolina and resettle on a reservation in Oklahoma. About one thousand Cherokees resisted and remained on the Eastern Seaboard until the early 1870s. As James Obadiah writes in the letter to JM Bryan, a representative of the Old Settler Cherokees, on October 1st, 1877, "And now after several years of poverty and disappointments we ask you to show to the President this same letter that induced us to emigrate here, and ask him to see that all that was promised us be made good." These "poverty" and "disappointments" refer to circumstances that made it necessary for the remaining Cherokees to leave their tribal land. By 1866, 125 Cherokees were killed by smallpox. Along with this outbreak, the community had other afflictions. Their fields were in ruins, plenty of soldiers who went to fight in the war were murdered, children were undernourished , and the community was plagued with factionalism. Their land was uninhabitable, and their community was barely functioning. In an attempt to save their community and people, they made the tough decision to make the arduous journey West.

In the same letter to JM Bryan, Obadiah explains, "We gathered up our families, and after encountering a great many hardships, finally reached here." Following suit with the Cherokees' treatment thus far, "hardships" were certainly faced on the West's journey. In the Spring of 1871, James Obadiah led 90 Cherokees en route to Oklahoma but paused in Loudon, Tennessee. They understandably wanted to continue the trip by rail, but the War Department wouldn't provide the transportation. Obadiah's group camped in the hot Tennessee countryside with no progress until October, when John D. Lang, who served on the Board of Indian Commissioners, accompanied the Cherokees on a train out West. After Obadiah's initial letter to JM Bryan about receiving the due compensation that was never paid, Bryan wrote to John D. Lang for the necessary verification to prove Obadiah's claim for the subsistence money. After Bryan never got a response from Lang, he reached out to someone who might have a better shot at receiving a response, William Stickney. In Stickney's letter to Lang, he asks Lang to recall the circumstances of Obadiah's service and to send a letter back to him, which he would then send back to Bryan. There is no record that Mr. Lang ever responded to either Stickney or Bryan. It remains unknown whether James Obadiah ever got his subsistence money or not. Obadiah did the best with the connections that he had to be able to obtain the money. His initial outreach and the ensuing chain reaction showed a strong self-advocacy.

The source from Obadiah gives us context to the lengths he had to go through to simply find a way to communicate to people in authority who could compensate him and his tribe. Despite obviously being in a position of low power, since Obadiah couldn't even contact Lang himself to get the verification, Obadiah continued fighting. In the face of adversity during this Reconstruction period, be it their inhospitable land, detrimental journey out West, or lack of compensation, Obadiah stayed strong and advocated for himself and those who traveled with him. The Cherokee's story of removal is similar to other tribes' who made the challenging journey West during Reconstruction, and had to continue fighting for basic rights.

Last Notes

We wanted to include this section to be cognizant that when talking specifically about marginalized communities that there are intersections within those identities and that the talk of representation is still from the point of view of a white man. Black women, Chinese women, people of color, immigrants, etc. all navigated this time uniquely and it would be a dishonor to generalize all experiences as one. Though we included as much that reflected these ideals, we implore you to look for these stories on your own.

THE OBADIAH LETTERS

If you're interested in taking a closer look at The Obadiah Letters, click on the images!

Letters from James Obadiah to Jeff Bryan, dated October 1, 1877. Letters from Jeff Bryan to William Stickey, dated April 30, 1878. James Obadiah Letters. American Indian Collection, Box 1, Folder 1. New-York Historical Society Library.

THINGS TO CONSIDER

You might have missed these three figures that are shown in the cartoon! It's important to note that when talking about unity and how that will look on a national scale, we have to consider the framework of America and how different forms of activism were established from one another. The three Presidents shown symbolize the ways in which American leadership has reflected what the people at the time needed the most and catalyzed into the movement and events we learn about now.

Presidents: Abraham Lincoln, George Washington and Ulysses S. Grant

WHO IS LEADING THE CONVERSATIONS NOW?

"The Thanksgiving Play" PLAYBILL

While Nast's cartoon intended to bridge the gap between all peoples and cultures with a Thanksgiving dinner, Native American Playwright Larissa FastHorse now emphasizes this same message regarding indigenous people today. A new, original off-broadway show, The Thanksgiving Play addresses the lack of representation of Native stories in the media. FastHorse's works had been turned down in the past because there weren't enough indigenous actors to play the parts. As a result, she took it as a challenge to share these Native stories with Native American actors.

The show has a satirical take on four white adults attempting to put on a Thanksgiving pageant, with their behavior being criticized from an indigenous person's perspective. It pokes fun at the characters' weak and glaring attempts of performative activism and pushes audience members to consider whose comfort we should be aware of. While humorous, it doesn't take away from the theme of challenging white institutions. It is even elementary school friendly, so a younger set of audience members can also learn this necessary message. The play serves to encourage other aspiring Native artists to honor their culture and pursue fields in the exclusive industry.

As Thomas Nast portrayed, all ethnicities, genders, and races had a stake in America’s future. Each community represented at the Thanksgiving dinner table had a unique narrative of growth during Reconstruction. Alongside Frederick Douglass, other leaders, including James Obadiah, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Ng Poon Chew, and Wong Chin Foo, were responsible for furthering the messages of universal suffrage, citizenship, and social equality reflected in Nast’s cartoon. These individuals laid the groundwork for social initiatives which evolved into the modern day movements that continue to strive toward the goal of composite nationality.

Thank you for reading!

Bess Spero Li, and Frank Roosa says: “Women's Rights and Reconstruction.” The Journal of the Civil War Era. The Journal of the Civil War Era, August 2, 2017. https://www.journalofthecivilwarera.org/forum-the-future-of-reconstruction-studies/womens-rights-and-reconstruction/ .

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, 1880, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/da/Elizabeth_Stanton.jpg

Frederick Douglass, 1879, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c5/Frederick_Douglass_%28circa_1879%29.jpg

Nast, Thomas, Alfred R. Waud, Henry L. Stephens, James E. Taylor, J. Hoover, George F. Crane, and Elizabeth White. “The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship Reconstruction and Its Aftermath.” Library of Congress, February 9, 1998. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/reconstruction.html

Russo, Gillian. “Why to See 'The Thanksgiving Play' on Broadway.” New York Theatre Guide. New York Theatre Guide, March 8, 2023. https://www.newyorktheatreguide.com/theatre-news/news/why-to-see-the-thanksgiving-play-on-broadway.

“South Carolina Freedpeople Demand Education.” Facing History & Ourselves, July 11, 2022. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/south-carolina-freedpeople-demand-education .

“Thanksgiving in North America: From Local Harvests to National Holiday.” Smithsonian Institution. Accessed May 3, 2023. https://www.si.edu/spotlight/thanksgiving/history.

“The History of Thanksgiving from the Native American Perspective.” Native Hope Blog, November 23, 2022. https://blog.nativehope.org/what-does-thanksgiving-mean-to-native-americans .

"The Making of the American Nation; a History for Elementary Schools," 1905, Redway, Jacques W., https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14778410491

"Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner," November 20th, 1869, Thomas Nast, https://loc.getarchive.net/media/uncle-sams-thanksgiving-dinner-th-nast

"Vintage Clip Art Table," Unknown, ND, https://pixabay.com/illustrations/table-vintage-folding-furniture-1952948/

“What the Black Man Wants.” Facing History & Ourselves, July 22, 2022. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/what-black-man-wants .

Wong Chin Foo, July 03, 2019, Scott D. Seligman 的, https://www.mocanyc.org/collections/stories/wong-chin-foo/