Eternos Caminhantes (The Eternal Wanderers), Lasar Segall

Introduction

Eternos caminhantes (The Eternal Wanderers), Lasar Segall, 1919

Jewish Lithuanian-born artist Lasar Segall in some ways spent his life wandering the globe, a theme present in both the content and history of his 1919 painting Eternos caminhantes or The Eternal Wanderers. Born under Russian Tzarist rule in 1889 (or 1891), Segall grew up in an environment that was unsafe and hostile to Jews. He moved to Berlin in 1906 to study art, eventually moving to Dresden in 1910 where the Academy of Fine Arts is more in line with his Modernist style. By 1912, he makes his first trip to São Paulo, Brazil, where much of his family had already moved. He is back in Dresden the next year however, where he spends the following years under various states of hardship: temporary house arrest due to his Lithuanian citizenship, loss of friends and colleagues due to war, and the Post-War economic downfall of Germany. In 1916, he is able to visit his hometown of Vilna, which is completely destroyed.

Over the next several years, his work takes on darker themes and an explicitly expressionist style. Eternos caminhantes is one such example from this period, and is part of a series that explores victims of the war. He is lauded as an Expressionist, and participates in influential artist groups. Eternos caminhantes is one of the first works acquired and displayed in the new Modernist Wing of the Dresden City Museum.

In 1923, Segall officially migrates to Brazil, and is immersed in the Modern Art scene in São Paulo. He ends up returning to Europe however, and forays into sculptural work in Paris between 1928 and 1932. He then spends the rest of his life in Brazil, where he dies in 1957. Throughout the latter years of his life he is a fierce advocate for Modern art in Brazil (which was not always friendly to the avant-garde), and continued to explore themes of Jewish suffering, loss, emigration, and outgroup identity within his own work. His home was transformed into Museo Lasar Segall, which opened in 1967.

Like Lasar Segall himself as well as the haunting figures represented in the painting, Eternos caminhantes has taken quite the journey. Initially celebrated, it was then confiscated and considered degenerate by the Nazi regime. Like Segall, the work ultimately ends up in Brazil.

Provenance

Dresden, Stadtmuseum

1919 - July 1937

Eternos caminhantes is acquired for the Modern Wing of the Dresden City Museum. Art historian, Paul Ferdinand Schmidt is director at the time. An advocate for Modern art, he was forced into retirement when the Nazis came to power. In 1921, Segall even painted a portrait, entitled Dr. P. F. Schmidt, where the art historian stands in front of Eternos caminhantes. This painting was lost in the war.

German Reich / Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, Berlin

July, 1937 - unknown

The work was officially seized from the public museum in 1937, although it had more or less been under Nazi control since 1933. It fell under the May 31, 1938 Law on Confiscation of Products of Degenerate Art which reads, “The products of degenerate art, which have been seized in museums and publicly accessible collections before the passing of this law and have been identified by authorities appointed by the Führer and Reich Chancellor can be seized without compensation on behalf of the Reich provided that they were guaranteed to be owned by nationals or domestic legal entities.”

Velten / Mark, depot for propaganda exhibitions Storage of the exhibits for the traveling exhibition "Degenerate Art"

1938 - unknown

The work was travelling in Degenerate Art exhibitions from 1933-1938 (see below) while under Nazi "ownership." It is said to have been placed in a storage depot in Velten, but not much else is known.

Basement of a High Nazi Official, unknown

unknown - after the war

Somehow, the piece ended up in the basement of a high ranking Nazi official, where it was discovered by French forces after the war. It was a recognized practice for Nazi officials to poach seized artworks for their personal collections, but any specific details about Eternos caminhantes are unknown.

Paris, Emeric Hahn

after the war - 1958

After being found by French troops after the war, the piece was transported to Paris and put up for auction to fund German war reparations. It was acquired by the Hungarian art dealer Emeric Hahn, who reached out to the artist in 1954 to confirm its authenticity (see letter above).

São Paulo, Museu Lasar Segall

1958 - present

In 1958, a year after Lasar Segall's death, Emeric Hahn sold Jenny Klasin Segall (Segall's widow) the painting for a price of $1,000. In 1967, Segall's home was converted into a museum, where the piece has remained since.

Degenerate Art Exhibitions

Frame sequence extracted from the film Zeitdokumente: Ausstellung "Entartete Kunst", 1933, Bundesarchiv - Koblenz.

From 1933-1938, while Eternos caminhantes was in Nazi possession, it moved around the regime in various travelling Degenerate Art exhibitions. Below is a visualization of known exhibitions where it was displayed.

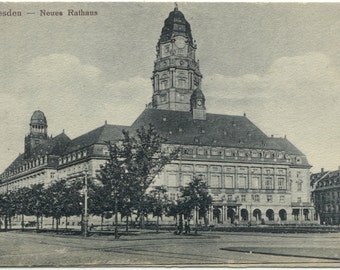

Degenerate Art (1.1), Dresden, New Town Hall, Atrium, 1933

Degenerate Art (1.2), Hagen, 1934

Degenerate Art (1.3), Nuremberg, Municipal Gallery, 1935

Degenerate Art (1.4), Dortmund, House of Art, 1935

Degenerate Art (1.9), Frankfurt am Main, Volksbildungsheim, 1936

Degenerate Art (2.1), Munich, Hofgarten-Arkaden, 1937

Degenerate Art (2.2), Berlin, House of Art, 1938

Degenerate Art (2.3), Leipzig, Grassi Museum, 1938

Degenerate Art (2.4), Düsseldorf, Kunstpalast, 1938

Sources

Museu Lasar Segall. “A ‘Arte Degenerada’ de Lasar Segall: Perseguição à Arte Moderna Em Tempos de Guerra.” Accessed December 1, 2021. http://www.mls.gov.br/exposicoes/temporarias/a-arte-degenerada-de-lasar-segall-perseguicao-a-arte-moderna-em-tempos-de-guerra-2/.

Barron, Stephanie. Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany. Los Angeles: Harry N. Abrams, 1991.

Cabañas, Kaira M. “Lasar Segall.” Artforum, Summer 2018. https://www.artforum.com/print/reviews/201806/lasar-segall-75607.

Otto Dix. “Catalog Item.” Accessed December 1, 2021. https://www.ottodix.org/catalog-item/.

“Confiscation,” November 26, 2009. https://www.geschkult.fu-berlin.de/en/e/db_entart_kunst/geschichte/beschlagnahme/index.html.

Costa, Helouise. A Arte Degenerada de Lasar Segall: Perseguição à Arte Moderna Em Tempos de Guerra., 2017. https://www.academia.edu/45524321/A_arte_degenerada_de_Lasar_Segall_persegui%C3%A7%C3%A3o_%C3%A0_arte_moderna_em_tempos_de_guerra.

Camden Civil Rights Project. “Eternal Wanderers,” November 23, 2015. https://camdencivilrightsproject.com/2-lasar-segall-eternal-wanderers-1919-2/.

“Freie Universität Berlin: Beschlagnahmeinventar ‘Entartete Kunst.’” Accessed December 1, 2021. http://emuseum.campus.fu-berlin.de/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=124808&viewType=detailView.

Kraftgenie. “Lasar Segall - The Eternal Wanderers.” Weimar (blog), August 10, 2010. http://weimarart.blogspot.com/2010/08/lasar-segall-eternal-wanderers.html.

Google Arts & Culture. “Lasar Segall Processes - Museu Lasar Segall.” Accessed December 1, 2021. https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/lasar-segall-processes/5gJyDOgp0pt5Lg.